Proof of the Vector Triple Product - Practice Questions & MCQ

Quick Facts

-

Vector Triple Product is considered one the most difficult concept.

-

35 Questions around this concept.

Solve by difficulty

The vectors are not perpendicular and

are two vectors satisfying:

and

. Then the vector

is equal to

Let $\vec{a}, \vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$ be vectors then a vector which is such that, it is not perpendicular to $\vec{c}$ and $\vec{a} \times \vec{b}$ together is

JEE Main 2026: Result OUT; Check Now | Final Answer Key Link

JEE Main 2026 Tools: College Predictor

JEE Main 2026: Session 2 Registration Link | Foreign Universities in India

$\vec{a} \times(\vec{b}+\vec{c})=$

If $\tilde{\mathrm{a}}=\mathrm{i}-\mathrm{j}-\mathrm{k}, \tilde{\mathrm{b}}=\mathrm{i}-\mathrm{j}+\mathrm{k}$ and $\tilde{\mathrm{c}}=\mathrm{i}+2 \mathrm{j}-\mathrm{k}$, then $\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})$ equals

Let $\vec{a}=\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k}, \vec{b}=3 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}$ and $\vec{c}$ be three vectors such that $\vec{c}$ is coplanar with $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$. If the vector $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{c}}$ is perpendicular to $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{b}}$ and $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{a}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{c}}=5$, then $|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{c}}|$ is equal to

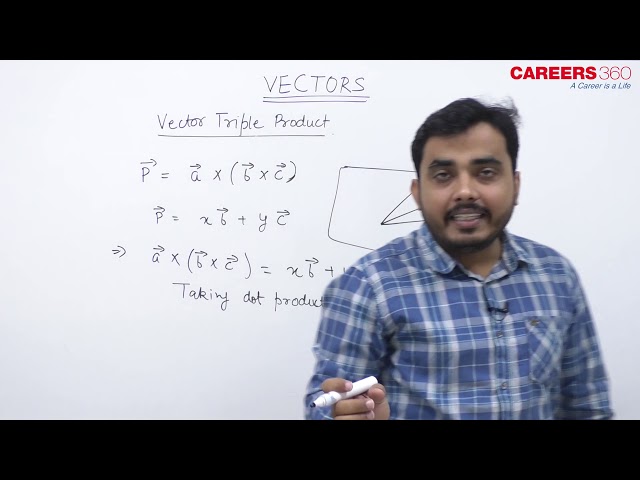

Concepts Covered - 1

For three vectors $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}}, \overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}}$ and $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}}$ vector triple product is defined as $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}})$. $\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \cdot \vec{b}-(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}) \cdot \vec{c}$

$\vec{p}=\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})$ is a vector perpendicular to $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b} \times \vec{c}$, but $\vec{b} \times \vec{c}$ is a vector perpendicular to the plane of $\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$. Hence, vector $\vec{p}$ must lie in the plane of $\vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$.

Let $\vec{p}=\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=l \vec{b}+m \vec{c} \quad[l, m$ are scalars $]$

Taking the dot product of eq (i) with $\vec{a}$, we get

$

\vec{p} \cdot \vec{a}=l(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b})+m(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c})

$

$

\left[\begin{array}{l}

\because \vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}) \text { is } \perp \vec{a} \\

\therefore \vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}) \cdot \vec{a}=0

\end{array}\right]

$

Therefore,

$

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & \vec{p} \cdot \vec{a}=0 \\

\Rightarrow & l(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b})=-m(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{1}{\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}}=\frac{-m}{\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}}=\lambda \\

\Rightarrow & l=\lambda(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \\

\text { and } & m=-\lambda(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b})

\end{array}

$

Substituting the value of $l$ and $m$ in Eq. (i), we get

$

\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=\lambda[(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \vec{b}-(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}) \vec{c}]

$

Here, the value of $\lambda$ can be determined by taking specific values of $\vec{a}, \vec{b}$ and $\vec{c}$.

The simplest way to determine $\boldsymbol{\lambda}$ is by taking specific vectors $\vec{a}=\hat{i}, \vec{b}=\hat{i}, \vec{c}=\hat{j}$.

We have,

$

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=\lambda[(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \vec{b}-(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}) \vec{c}] \\

& \hat{i} \times(\hat{i} \times \hat{j})=\lambda[(\hat{i} \cdot \hat{j}) \hat{i}-(\hat{i} \cdot \hat{i}) \hat{j}] \\

& \hat{i} \times \hat{k}=\lambda[(0) \hat{i}-(1) \hat{j}] \Rightarrow-\hat{j}=-\lambda \hat{j} \\

\therefore \quad & \lambda=1

\end{aligned}

$

Hence,

$

\vec{a} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \vec{b}-(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}) \vec{c}

$

NOTE:

1.

$

\begin{aligned}

& \overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{c}) \cdot \vec{b}-(\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b}) \cdot \vec{c} \\

& (\vec{a} \times \vec{b}) \times \vec{c}=(\vec{c} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}}) \cdot \vec{b}-(\vec{c} \cdot \vec{b}) \cdot \vec{a}

\end{aligned}

$

2. In general $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}}) \neq(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}}) \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}}$ If $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}})=(\overrightarrow{\mathbf{a}} \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{b}}) \times \overrightarrow{\mathbf{c}}$ then the vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{c}$ are collinear.

Study it with Videos

"Stay in the loop. Receive exam news, study resources, and expert advice!"